I’ve written a lot about GOAT’s book scanning activities for our archival work, but today have another kind of scanning to talk about! Last week I met with @CriptasticHacker from C.R.I.P.S.R.I.S.E., to walk through the process of scanning a physical object for 3D printing. Buckle up, this is nerdy as hell!

First of all I would like to show off the useful object that @CriptasticHacker brought to show me. His Whill powerchair joystick was slipping around, so he took it apart and had a look. It turns out the inside of the joystick has a plastic part that snaps onto a metal post. Because of the way it is designed, you can change the orientation of the joystick from vertical to horizontal so it fits your hand for steering. Over time though, and daily use, bits of that plastic part wore away so that the joystick slid around uncontrollably, making it hard to drive accurately. So he scanned that part, redesigned it, and 3D printed it.

Here’s a comparison of the old and new parts side by side:

Pretty cool isn’t it?!

@CriptasticHacker is largely self taught over many years of watching free online videos and experimentation at home. There are also local and worldwide 3D scanning and printing communities where he has gotten advice and other resources.

His original setup was a Creality Ferret, an infrared only scanner which you can buy for around $150. Very affordable! For this demo, he brought over a borrowed Creality Raptor, more expensive and more accurate which can do infra scans but also a blue laser scan. The Raptor is larger than the Ferret, but still quite portable. Along with that, he had a small turntable with dotted “reference points” on it in a regular pattern. (That turntable was made from 3D printed parts!)

There are also other accessories, like a carrying case, a portable handheld gizmo that looks like the things they use to do checkout in grocery store, tripods, etc. and extra stickers with more reference dots you can put onto larger objects that don’t fit onto the turntable. There is also an infrared spray But for this demo we stuck with the basics!

Our first step was for me to install the free Creality scanning software. With my 5 year old MacBook Air and a decent wifi connection this took just a few minutes to download and install. This software connected to the Raptor easily.

I was excited to try to scan something small but complicated. In a project bag I had out I happened to have an old prescription bottle with some screws in it so we took off the cap.

For people who may not be familiar with the free/open culture and “open source” vibe, I should explain that I 100% expected that someone, in fact multiple people, around the world have already scanned, cleaned up, and published designs for this exact sort of standard medicine bottle cap. That turned out to be true! Here are some examples from Thingiverse, Printables, and Yeggi, which are some popular platforms for designers to share their creations with the world, as a public good, often under Creative Commons licenses.

The software seemed pretty mysterious to me, but @CriptasticHacker walked me through the basic settings. For an older computer he recommends setting the resolution of the scan to lower than the default of .15mm; something more like .5mm. A lower resolution and lower frame rate means less precision for the final design and print, but also means a quicker scan time, and smaller file sizes and faster processing for the software tricks we were about to perform. I wanted to try with the defaults of .15mm resolution and 23fps frame rate, which luckily my computer was easily able to handle.

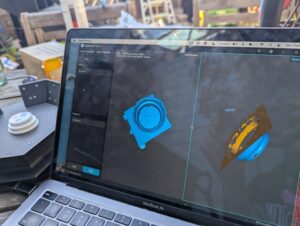

Our next step was to put the object on the turntable, hit “scan”, and turn the dolly slowly. As that happens, the image of the medicine bottle cap formed on my laptop screen first in an orange outline and then in blue “paint” as the surface was mapped more precisely. The goal of the scans is to get everything mapped in blue, as much as possible.

We then stopped the scan and started a new scan with the cap flipped over. I wasn’t going for production quality — just enough to give me an idea of what it took to do a decent scan. Our two scans were about 300MB each.

With these two initial scans, the next step was to eliminate everything that wasn’t the stuff we wanted to print. That meant a pretty clunky process of lassoing and deleting parts of the image with a non-ideal navigation menu. Good luck with this if you don’t have great hand dexterity – if so, you will need to partner with someone else to massage your image files! I gave it a quick stab.

After the image cleanup, you have to match up the files so that they line up properly. In this case, we needed a point on top of the cap and at least two other points, to match points on the bottom. Our first two tries sucked, but then we kind of figured out how to align the files well enough to merge, or fuse, the two images. The end result was a 3-d looking object, a bit raggedy, but recognizable a screw top lid for a medicine bottle. We then exported this as an STL file which turned out to be about 5MB. Much better than the 600MB scan files we were manipulating in Creality’s software! STL files are a common format used by 3D printers.

From there, we uploaded the STL file into a CAD program. There are tons of CAD programs and people spend years becoming great at using them! Some are expensive but there are also free options. @CriptasticHacker showed me a free CAD program called TinkerCAD, that works in a web browser and that I think may be meant for children or at least, for educational settings. In this program we could further edit and manipulate our 3d printing file. So, for example, I could click on the pre-set shape options in TinkerCAD’s menu and drag a 3-d blob or some text over to the top of our bottle cap to add it.

It was really fun just being able to rotate and zoom in on this virtual object, and I felt like a wild, futuristic wizard doing it!!

If you weren’t actually scanning, and instead started with a base STL file, say, that you downloaded from Thingiverse or a similar platform, you could modify the file, add raised text or a more grabbable shape easily to the bottle cap. Then, you could export that new STL file and print it on a 3D printer.

And that’s another post for the future, when I will go through some of the printing process with C.R.I.P.S.R.I.S.E.!

There are other options that don’t require you to own a 3D printer and learn to use it. Local libraries or schools or makerspaces may have 3D printers, or experts to set them up and help you print. Under the U.S. Assistive Technology Act, there are programs in some states to provide 3D printed assistive tech for people, like TechOWL/CreATeLabs in Pennsylvania or WATAP in Washington state. Makers Making Change has many people who may 3D print stuff for you for free or a small fee.

Other options include looking for local or far-flung printing labs who will make stuff for you for a fee. I have not tried this yet, but am told that it has become surprisingly affordable and can be worth it for custom parts. Some that we talked about: Proto Labs, Makelab, Shapeways, Xometry, and JLC 3d Prints.

You can also print in different materials depending on what you need. PetG or PLA filament, nylon (tougher, but slower to print and needs a lot of ventilation to avoid fumes) or carbon fiber (toughest but also slowest).

A final thought form Criptastic Hacker and C.R.I.P.S.R.I.S.E.:

Disabled people deserve to have customized stuff! Not rattling half broken things that don’t suit our needs!

very cool! Will this file be uploaded anywhere for folks to grab and play around with?

Yes, the joystick one will be uploaded, but the medicine bottle cap won’t be, it was just a really rough demo and we didn’t make it finished quality!

Here are the files to print the WHILL joystick insert! https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:7193879